David S. Garnett is a British science fiction author who wrote his first novel at 19. It was published by the first American publisher he sent it to.

He started by writing short stories which were always sent to Michael Moorcock, editor of the legendary/notorious sf magazine New Worlds. Moorcock always sent them back, the first one with a note of encouragement, the second one with a longer note, the third one, etc.

He started by writing short stories which were always sent to Michael Moorcock, editor of the legendary/notorious sf magazine New Worlds. Moorcock always sent them back, the first one with a note of encouragement, the second one with a longer note, the third one, etc.

Then Garnett wrote a novel. It took six weeks. He sent it to Berkley Books in New York, who bought it. The book was Mirror in the Sky by Dav Garnett.

The name “Dav” (a word designed to be read rather than pronounced) was used to distinguish him from another David Garnett, an author born in 1891. A member of the Bloomsbury group, an artistic and literary circle, one of his novels (Aspects of Love ) later became an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical. But back to David with an “S.” . . .

Mirror in the Sky was also published in Swedish and German (the first of over two dozen languages into which his novels and stories have been translated) and a film option was sold to a Hollywood production company. Four years after the American edition, Mirror was published in the UK by Robert Hale, which specialised in producing hardback editions for libraries. It came out under the name David S. Garnett.

Mirror in the Sky was also published in Swedish and German (the first of over two dozen languages into which his novels and stories have been translated) and a film option was sold to a Hollywood production company. Four years after the American edition, Mirror was published in the UK by Robert Hale, which specialised in producing hardback editions for libraries. It came out under the name David S. Garnett.

The “S.” is for Stanley and, despite a family connection with Accrington, he insists he was not named after the Lancashire town’s famous football team.

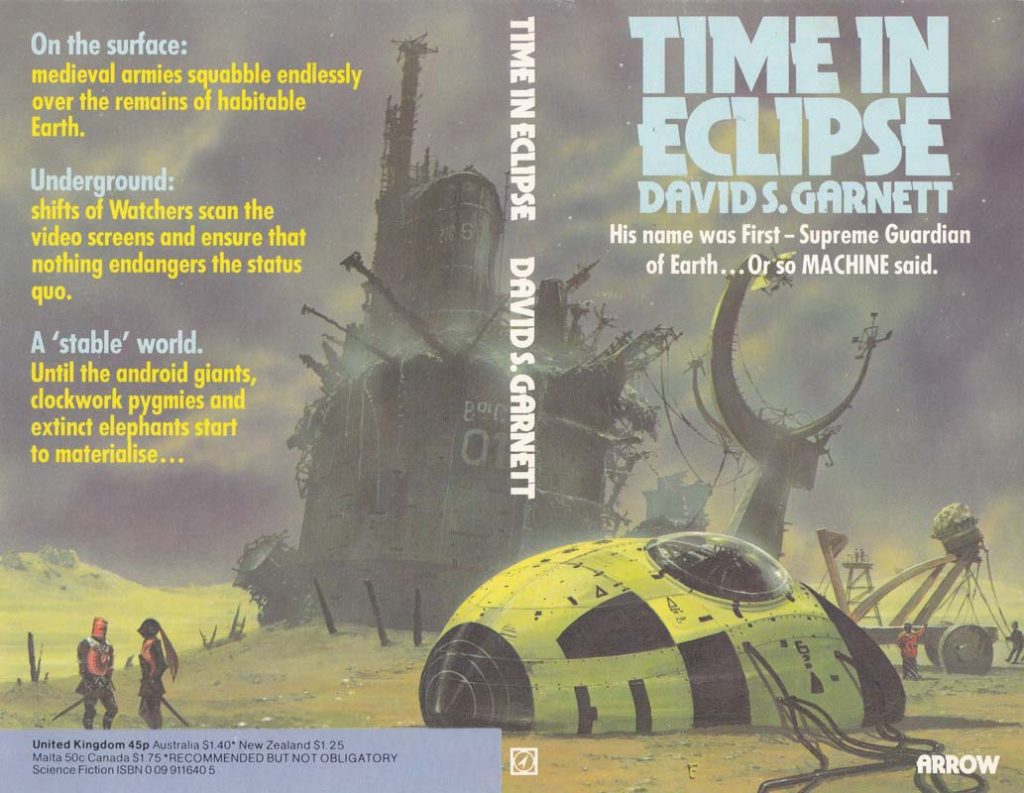

A few more sf novels followed from Hale, mostly routine adventures. A more ambitious work was Time in Eclipse, which later became an Arrow paperback and was also published in Germany and Italy.

Eclipse was set in a post-apocalyptic Europe which has reverted to medievalism but is under constant observation by an advanced subterranean society. There are aliens and time travel, clockwork elephants and android pygmies, and an amnesiac lead character who is manipulated by a machine intelligence. All in 176 pages. Time in Eclipse was the last of Garnett’s early science fiction novels, written when he was 23.

After that most of his writing time was spent on Other Things, the kind of work which many a freelance author has to produce to put muesli on the table and beer in the glass: magazine articles and stories, reviews and interviews, books on films and long-forgotten pop groups, work for radio and television (including cutting out ninety percent of a Dickens novel for the BBC), ghost writing for an author too busy to write his own books, etc. Garnett wrote quite a bit, and at one time he was writing seven books for three different publishers. He once had short stories in three different monthly magazines, all on sale simultaneously. Which is why he needed a few pen names.

Although no longer producing sf novels, he was still writing (and even occasionally publishing) the odd (and occasionally very odd) sf short story. Although pirated versions of some are on the cybernet, until now only one such story has been authorised: “Off the Track” was originally published in Interzone, translated into German (“Abseits der Straße”), and later reprinted in The Best of Interzone. It can be read on the Infinity Plus website here = off-the-track

Although no longer producing sf novels, he was still writing (and even occasionally publishing) the odd (and occasionally very odd) sf short story. Although pirated versions of some are on the cybernet, until now only one such story has been authorised: “Off the Track” was originally published in Interzone, translated into German (“Abseits der Straße”), and later reprinted in The Best of Interzone. It can be read on the Infinity Plus website here = off-the-track

One of Garnett’s stories, “Still Life”, made it onto the final ballot for science fiction’s top prize, the Hugo Award, for best short story. At the World SF Convention in Brighton, it was voted the world’s fourth best sf short story. There were five stories on the ballot, so at least it wasn’t last.

Originally published in the USA, in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, “Still Life” was later translated into French (“Nature Morte”) and German (“Stilleben”). It can now be found (in English!) here = still-life

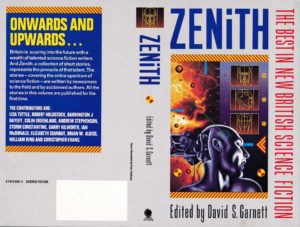

Then, as well being a writer, Garnett became an editor when he was asked by Sphere Books to compile a collection of new sf by British authors. This became Zenith, and half its stories became prize nominees/winners or were reprinted in best-of-the-year collections – or both. Zenith 2 followed, but by then Sphere had been taken over and the book was published under the Orbit imprint.

Then, as well being a writer, Garnett became an editor when he was asked by Sphere Books to compile a collection of new sf by British authors. This became Zenith, and half its stories became prize nominees/winners or were reprinted in best-of-the-year collections – or both. Zenith 2 followed, but by then Sphere had been taken over and the book was published under the Orbit imprint.

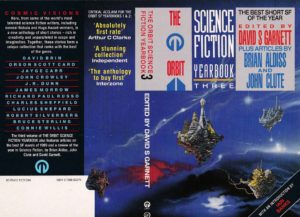

Meanwhile, Garnett had come up with an idea for a new best-of-the-year’s-sf anthology. This was The Orbit SF Yearbook, and three volumes had been commissioned. But Orbit didn’t want to publish two sf collections a year, and the option on Zenith 3 was dropped.

Years earlier, Garnett had started out by submitting stories to Michael Moorcock. Now the situation was reversed, with Moorcock sending a story to Garnett – but with more success. Moorcock’s “The Cairene Purse” was published in Zenith 2.

Years earlier, Garnett had started out by submitting stories to Michael Moorcock. Now the situation was reversed, with Moorcock sending a story to Garnett – but with more success. Moorcock’s “The Cairene Purse” was published in Zenith 2.

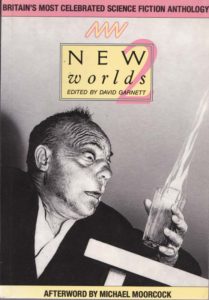

When Zenith was cancelled, Moorcock (who still owned the rights to the New Worlds title) offered Garnett the chance to start a new paperback series of NW. But first he had to find a publisher – and Gollancz agreed to bring out four new volumes. Garnett never had one of his own stories in New Worlds but now he was the editor. Which was almost as good.

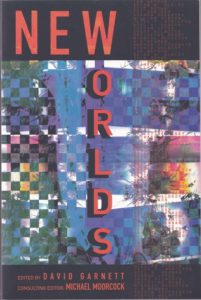

Gollancz published the new four collections to great acclaim, and then the American publisher White Wolf agreed to publish four more. This was to be the first time the title originated in the USA, but when the contract came through it was for only two volumes. In the event, White Wolf only published one, and this was to be the last book of short stories that Garnett edited.

New Worlds was first published in 1946, and was one of the most significant publications in the evolution of contemporary science fiction. Its title alone had so much resonance that so many writers have said: “I always wanted to be in New Worlds.” One such was William Gibson, author of Neuromancer, who contributed a piece to the White Wolf volume. Read more about NW here = new-worlds

New Worlds was first published in 1946, and was one of the most significant publications in the evolution of contemporary science fiction. Its title alone had so much resonance that so many writers have said: “I always wanted to be in New Worlds.” One such was William Gibson, author of Neuromancer, who contributed a piece to the White Wolf volume. Read more about NW here = new-worlds

Editing three series of anthologies led to Garnett being head-hunted by one of the most famous British publishing houses. They had previously published some science fiction titles but now wanted to develop a major list, and Garnett was asked if he was interested in being considered as their consultant editor. It was to have been a part-time job, in theory, but by now he was well aware how long editing could take.

Each of his ten sf collections had probably cost Garnett as much time as writing a book. (His loss, literature’s gain.) He said no to becoming a consultant editor – and the publisher never started its new sf list.

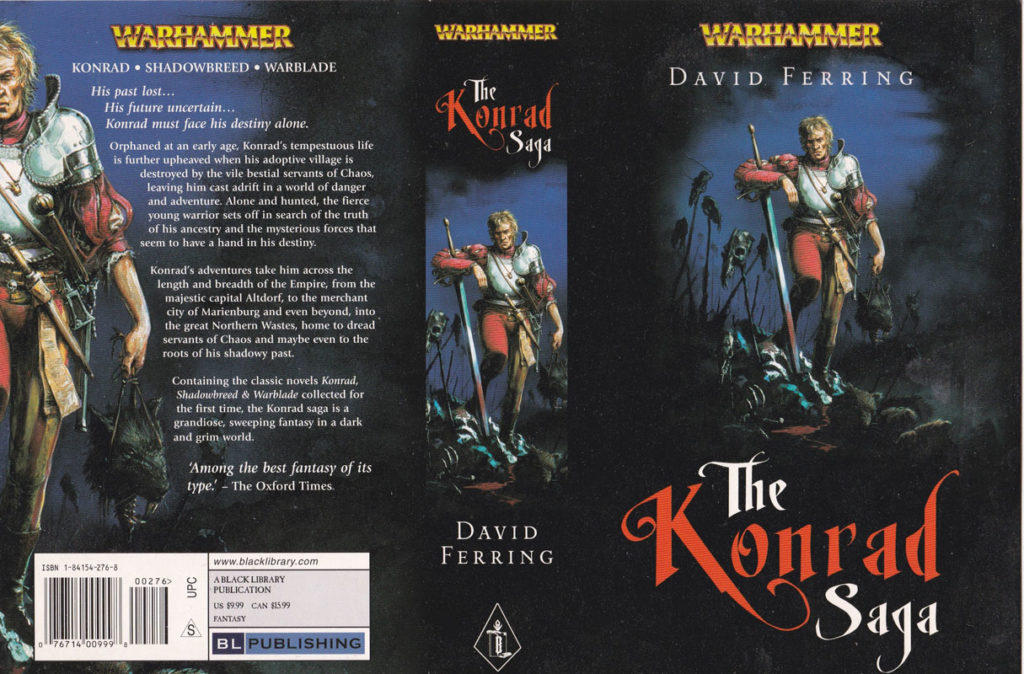

Around the same time as the anthologies, Garnett was also writing a fantasy trilogy for Games Workshop. These were based on the company’s table-top game Warhammer. Gaming novels had a reputation in the publishing world for poor quality. To counter this, GW hired David Pringle, editor of Interzone to find authors who could produce gaming books of a much higher standard. Pringle approached a few Interzone authors, including Garnett, who asked the most vital literary question: “How much are they paying?”

Around the same time as the anthologies, Garnett was also writing a fantasy trilogy for Games Workshop. These were based on the company’s table-top game Warhammer. Gaming novels had a reputation in the publishing world for poor quality. To counter this, GW hired David Pringle, editor of Interzone to find authors who could produce gaming books of a much higher standard. Pringle approached a few Interzone authors, including Garnett, who asked the most vital literary question: “How much are they paying?”

It turned out that GW were backing up their ambitions with a financial offer which was hard to resist, and Garnett signed to write three Warhammer novels. These were Konrad, Shadowbreed and Warblade by “David Ferring”.

There are various reasons why a writer might use a pseudonym. For example: a magazine editor might be short of material for one issue and need to use two pieces by the same writer, in which case a pen name is called for. Or it is not unknown for an editor to take a totally unwarranted dislike to a writer and refuse to publish anything by him/her ever again. If the author has an agent, he/she can simply invent a new pseudonym and the agent can continue sending (and selling) material to the unwitting editor.

There are various reasons why a writer might use a pseudonym. For example: a magazine editor might be short of material for one issue and need to use two pieces by the same writer, in which case a pen name is called for. Or it is not unknown for an editor to take a totally unwarranted dislike to a writer and refuse to publish anything by him/her ever again. If the author has an agent, he/she can simply invent a new pseudonym and the agent can continue sending (and selling) material to the unwitting editor.

But the most common reason for using a pseudonym is to differentiate between the types of material a writer produces – and a trilogy of fantasy novels based on the Warhammer world was a long way from the science fiction for which Garnett reserved his own name. Not that this made any difference to Games Workshop, who immediately announced the real name of the auteur behind the Ferring nom de plume.

The trilogy went through several UK/US editions and reprints, and was translated into Czech, German, Hungarian, Polish and Russian. They were later published in a single volume, The Konrad Saga (also in Germany, Konrad der Krieger). Despite its success, the series has long been out of print as the books are no longer compatible with current Warhammer ideology.

The Konrad Saga is for sale on Amazon. (Other book sites are available). It’s a good read – and current prices for a previously enjoyed copy are upwards of £40.

Also available from Amazon, but at a more reasonable cost, are the Kindle editions of David Garnett’s comedy sf books: Stargonauts, Bikini Planet and Space Wasters. Yes, there are three of them, all set in the same bizarre comic future, but Garnett claims this is not a trilogy. (Read about each of the trio elsewhere on this website.)

David S. Garnett is currently waiting for Andrew Lloyd Webber to get in touch with a proposal for Bikini Planet: the Musical.

Cover credits: Mirror in the Sky (USA), Richard M Powers; Spegel I Skyn (Sweden) unknown; Time in Eclipse (UK), Chris Foss; Eclissi Temporale (Italy),G Berni; Zenith, Peter Gudynas: The Orbit Science Fiction Yearbook #3, unknown; New Worlds #2, Jim Burns; New Worlds (USA), unknown; Mirror in the Sky (UK), Laurence Cutting; The Konrad Saga, David Gallagher; Bikini Planet (USA), Patrick Jones.